Slugs are our worst enemy, and this year, they are everywhere! I wish that getting rid of them were as simple as just carrying a salt shaker around the farm with me, but unfortunately, I think that that would only work in a cartoon. To be completely fair, it’s not the slugs themselves that I have a problem with, it’s the deadly parasites that they carry.

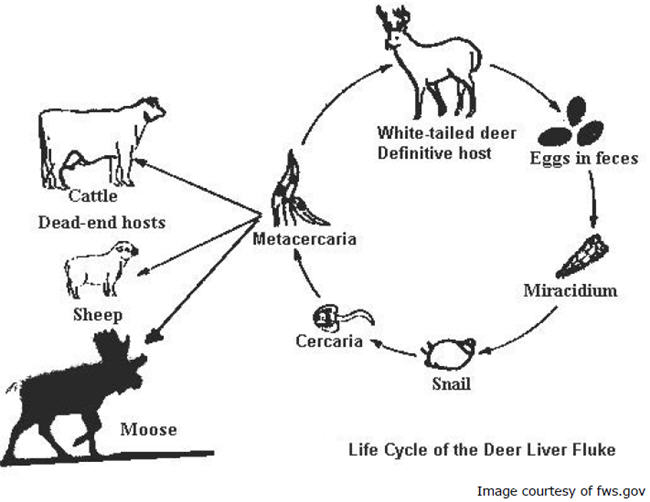

Slugs (and freshwater snails) serve as the intermediate host for a parasite called Fascioloides magna, more commonly known as liver fluke. In our area, this parasite is principally found in whitetailed deer, but it can also be transmitted by elk and caribou. Fascioloides magna is a flatworm that resides in the liver of a host animal and releases eggs that are passed through the host animal’s feces. Outside of the host animal, the eggs hatch into larvae, which then find a slug to reside in as they continue to develop. Once the larvae mature, they are released from the slug and attach themselves to a plant, which is then eaten by a ruminant, who will become the parasites’ next host. All of that may sound a bit complicated, so I’ve included a graphic below that I borrowed from the Pennsylvania Game Commission website to try to clarify things.

Interestingly, it seems that the deer that spread liver fluke rarely exhibit clinical symptoms of infestation themselves, but the same cannot be said for domestic ruminants like cattle, sheep, and goats. In these species, liver fluke can cause productive losses in the form of reduced milk production, stunted growth, and weak offspring. Liver flukes can also cause extensive liver damage that can ultimately lead to death, particularly in small ruminants. Fluke infestation can be difficult to diagnose because it requires postmortem examination of the liver, so unless animals are being sent for slaughter, it can take a lifetime to get a definitive answer. Unfortunately, we are certain that liver fluke is an issue on our farm, as we have had two animals with evidence of fluke migratory pathways in the liver upon necropsy.

Combatting liver fluke may be even more difficult than diagnosing it. It would be impossible to eradicate all of the deer and all of the slugs in the vicinity of our farm, and even if it were possible, eradicating an entire native species does not fit within our farm’s vision of practicing regenerative agriculture. Whether we like it or not, these creatures belong here, so we must find ways to work around them. Our primary strategy is to reduce the likelihood that our animals will be exposed to liver fluke by managing their grazing more carefully. Slugs thrive in wet ground, so we have been closely monitoring the moisture of our soil and restricting access to the wettest areas. This year, the weather has not been on our side at all. With flooding in early July and torrential rains that seem to have been coming every few days since, our soil hasn’t had much of a chance to dry out, so we have been keeping most of our animals close to the barn where it is relatively high and dry. It has been frustrating to see our pastures go so underutilized, but our animals’ health is our first priority.

Not only does liver fluke adversely affect livestock, it affects moose as well. A joint project conducted by researchers from Cornell University and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) revealed that liver fluke may have been responsible for 21% of the deaths in the moose that were studied. Earlier in 2023, the Adirondack Daily Enterprise reported that a young moose that was part of the DEC’s Adirondack Moose Project was recovered for necropsy after it died in nearby Onchiota, and it was determined that liver fluke was the cause of death.

For more on deer liver fluke, check out this fact sheet from the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Health Diagnostic Center:

https://cwhl.vet.cornell.edu/system/files/public/cwhl-fact-sheets-giant-liver-fluke.pdf